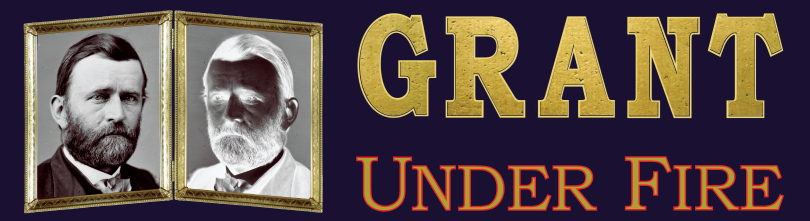

Yesterday, I helped confirm one of the many smaller points that Grant Under Fire makes. General Joe Hooker is often criticized for trying it on with his superior, Ulysses S. Grant, on November 21, 1863 at Stevenson, Ala., while the latter was on his way to Chattanooga, Tenn. When Hooker sent a staff officer and wagon to take Grant from the railroad station to Hooker’s headquarters, Grant responded: “If Gen. Hooker wishes to see me he will find me on this train.” Hooker soon came to present his respects.

But instead of some studied insult, by Hooker’s not appearing at the railroad station to wait on Grant in person, it is evident that Grant was expected to stop at Stevenson. He had written to Burnside that, “I will be in Stevenson tomorrow night and Chattanooga the next night.” At the New-York Historical Society, I just saw a copy of Secretary Stanton’s telegram from Louisville, informing the War Department that “General Grant reached Nashville safely yesterday. I have dispatch from him stating that he will go on to Stevenson to day and thence to Chattanooga fast as possible.” So, if Hooker was expecting Grant to stay the night in Stevenson, his sending a staff officer to escort Grant to Hooker’s headquarters seems completely appropriate (unless one thinks that Hooker should have been at the railroad station waiting for Grant the whole time, as opposed to tending to his headquarters duties). And wouldn’t Grant want to visit headquarters in order to learn about an important component of his brand new command?

Many Grant biographers indict Hooker for supposedly disrespecting Grant, in this scenario, which then makes it easier to justify Grant’s later mistreatment of Hooker (trying to get rid of him and then trying to keep him out of the upcoming battle at Chattanooga). This affair is analogous to other incidents in which certain officers are accused of supposedly disrespecting Grant and, thus, they deserved their comeuppance: Don Carlos Buell’s not reporting to Grant at Savannah, Tenn., prior to the battle of Shiloh; William Rosecrans’ feeding a correspondent tales about Grant’s drinking; George Thomas’ not offering a wet and dirty Grant dry clothes and food upon the latter’s arrival in Chattanooga; and Winfield Scott Hancock’s not saluting Grant on a Washington, D.C., street. Grant Under Fire helps to redeem these various officers from the undue criticisms of Grant and his biographers.

While there is justification to explain Hooker’s actions as appropriate, his earlier record as a subordinate commander raises questions about his loyalties within the chain of command. During the Fredericksburg campaign, at times he intrigued against his commander General Ambrose Burnside. The insubordination was even mentioned in Lincoln’s letter appointing Hooker to the command of the Army of the Potomac earlier that same year. Hooker’s failure to personally await Grant’s arrival at the railroad strikes me as following the same pattern, subtly holding himself above true subordination. General Oliver Howard who came west with Hooker as commander of 11th Corps was at the railroad encounter. When Grant took the opportunity to assert himself, Howard believed he was justified to “gain the proper ascendency”.

Dan, thanks. Oliver O. Howard, of course, didn’t get along with Hooker, and he offered a large number of slightly varying versions of this encounter.

If Grant had stated that he was planning on staying at Stevenson, or even just visiting there on his way through, I still don’t see the necessity of Hooker, the local commander, remaining at the railroad station in waiting, when the superior officer would be going to his headquarters after getting off the train.

I think that Grant knew that Halleck was heading to Pittsburg Landing after the Battle of Shiloh, but I certainly wouldn’t expect Grant to be hanging out at the landing waiting for Halleck’s boat to show up, just so he could pay his compliments.